Source: Deadline

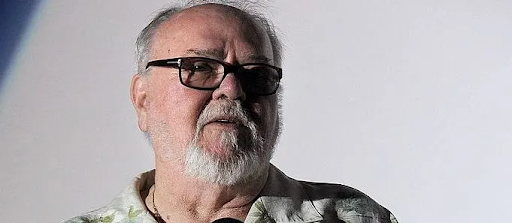

The work of a film editor may not always get the credit that it so often deserves, but without it, the art of cinema as it’s currently known would not exist, let alone be so universally revered. Before the invention of film editing, most filmmakers could only make films that were at most a few minutes long and showed a single perspective of a given subject; while the likes of Georges Melies were able to get slightly creative with their camera work and work around this issue to a certain extent, most cameras had to remain firmly in place and could not show more than one specific event at a time. It was only when filmmakers realized that one could cut and arrange different pieces of film into a specific order and use such combinations to tell longer and more substantial stories that the cinematic medium truly came alive. To this day, editing remains a necessary part of the post-production process, and while they may not always receive the name recognition of actors, directors, or other more widely admired individuals, there are those that are still looked up to as pioneers of the art form. These include Thelma Schoonmaker, who can claim credit for the assembly of countless Martin Scorsese features; Walter Murch, a frequent collaborator with Francis Ford Coppola who put together “The Godfather” and its sequels; Jennifer Lame, the most recent winner of the Academy Award for Best Film Editing for her work on Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer”; and finally, an editor who sadly passed away just recently at the ripe age of 88, Bud S. Smith.

Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma on December 6th, 1935, Smith began his career in the film industry in 1963, working his way through the editorial department before earning his first job as the chief editor of a feature in 1969. It was during that year that Smith assembled Robert Downey, Sr.’s comedic satire “Putney Swope”, which stars Arnold Johnson as a black advertising executive who’s voted chairman of the board and uses his new position of power to take his company in bold and audacious directions. Though a relatively small production (budgeted at only around $120,000), the film proved solid enough for Downey, Sr.’s liking that he asked Smith to edit his next two features: “Pound” in 1970 and “Greaser’s Palace” in 1972. It wasn’t until a year later in 1973 that Smith’s career truly took a turn for the better when he was hired to edit three films that were to be released that year: Vernon Zimmerman’s road comedy “Deadhead Miles”, another Robert Downey, Sr. film that was titled “Sticks and Bones” and made its premiere on television that summer; and a film that is arguably still Smith’s most widely praised work to date, William Friedkin’s supernatural horror classic “The Exorcist”.

One cannot overstate just how big of a hit “The Exorcist” was when it made its debut during the Christmas season of 1973; in fact, when adjusted for inflation, its box office gross is still among the ten highest of any feature film released in the United States. More importantly, while the film was certainly not without its controversies, reception from critics and audiences was generally very positive, enough for the film to ultimately receive ten Academy Award nominations (one of them being Best Picture) during the following year’s ceremony. Smith was one of the people who receives an Oscar nomination for his contributions to “The Exorcist”, nominated alongside Evan A. Lottman and Norman Gay in the category for Best Film Editing (ultimately losing to Carl and Harold F. Kress for “The Towering Inferno”). Smith’s editorial work for “The Exorcist” was so exceptional that he became one of Friedkin’s most frequent collaborators, working with the director on films like 1977’s “Sorcerer”, 1980’s “Cruising”, and 1985’s “To Live and Die in L.A.” among others.

“The Exorcist” would not be the only instance in which the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science would consider recognizing Smith’s work as an editor. About a decade after that film came the 1983 dance drama “Flashdance” directed by Adrian Lyne; while reviews of the feature were largely negative, there was a great deal of praise directed to various aspects of its technical craftsmanship, particularly Smith and fellow editor Walt Mulconery’s arrangement of the many tightly edited dance sequences that can be seen throughout. Smith was once again nominated for a Best Film Editing Academy Award for his work on this film, losing this time to the five-person team made up of Glenn Farr, Lisa Fruchtman, Stephen A. Rotter, Douglas Stewart, and Tom Rolf for “The Right Stuff”. Smith and Mulroney, were however, able to win the BAFTA for this exact same category, so they did not exit that year’s award ceremony completely empty-handed.

Apart from the previously discussed features, Smith’s biggest claim to fame as an editor may be the 1984 martial arts drama “The Karate Kid”, which continues to be thought of as a bona fide classic of the 1980s. It also happens to be the second film of his that he was also credited as producer; the first of these was the aforementioned “Sorcerer”, and in the following years, Smith would continue to be listed as producer in such films as Friedkin’s 1986 television film “C.A.T. Squad” and Tim Sullivan’s 2006 horror film “Driftwood”. Still, as much as Smith would serve as producer for certain feature films (especially during the later stages of his career), he continued to primarily work as an editor, with the 2005 sports drama “The Game of Their Lives” being the final film for which Smith served as an editor.

In 2012, Smith was unfortunately diagnosed with throat cancer, a condition that more or less brought what remained of his capability to work to an end. Smith would ultimately survive for another twelve years before passing away in his Studio City home on June 23rd after succumbing to respiratory failure. He is survived by his wife Lucy Coldsnow-Smith, who had previously worked as a dialogue editor on such films as “Boyz n the Hood” and “Million Dollar Baby” among many others. Like many great creators, Smith may no longer be among the living, but his contributions to the cinematic medium will keep his legacy alive for several years to come.