February 2020 has come at last, and with it comes an abundance of holidays: Valentine’s Day, President’s Day, and even a holiday dedicated to a furry brown rodent that made a movie with Bill Murray. Going on throughout the entire month, however, is something arguably more important: a commemoration of African-Americans and their history. With Black History Month having officially begun and continuing throughout the month (and, thanks to the leap year, extending by one more day than usual), the time has come for us to look back at some of the artistic achievements that black people have contributed to the world. As our primary area of interest is independent film, World Wide Motion Pictures has opted to showcase the best that black filmmakers have brought to the world of cinema. There are plenty of films that we’d be happy to introduce, but here are some of the films that we feel best demonstrate why black cinema deserves to be prominently featured as part of an ongoing discussion of film history.

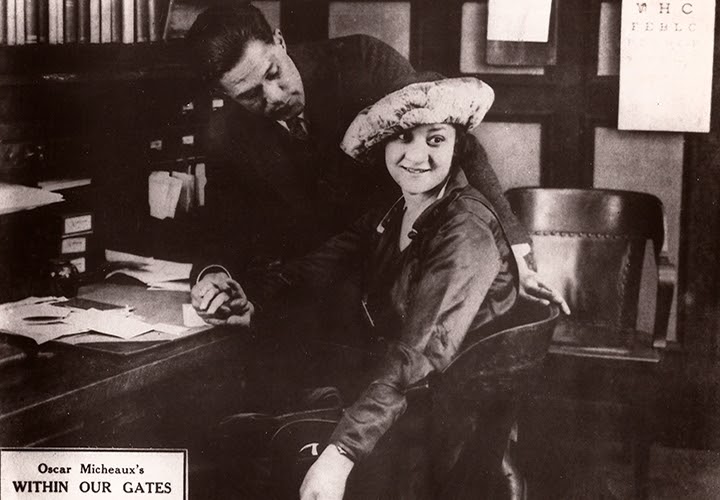

Within Our Gates (1920) – One of the earliest achievements of black cinema, this silent era gem tells of a young biracial woman fighting to raise money for her local school and falling for a handsome black doctor along the way. Brought to us by director Oscar Micheaux, whose Chicago-based Micheaux Film and Book Company of Sioux City was one of the first film studios to be run by black filmmakers, the film was made in large response to the previous year’s Birth of a Nation, which was lauded for it cinematic innovations but criticized for its racist depictions of African-Americans. Dealing with themes such as interracial romance, sexual assault, and the underfunding of the education system, the film remains just as poignant now as it did a century ago.

Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1967) – The 1960’s saw the rise of black documentarians like Madeline Anderson and St. Clair Bourne, whose films provided a direct insight into the trials and turmoil of the Civil Rights Movement. Perhaps the most ambitious of these documentaries came from filmmaker William Greaves, with an experimental film that follows a number of actors in Central Park as they perform the same scene of a marital break-up and shoot the scene repeatedly throughout the day. Metatextual on multiple levels in how it dissects the filmmaking process, the film ends up as a documentary within a documentary within a documentary, and its surreal yet fascinating presentation continues to serve as an inspiration for future experimental filmmaking.

Watermelon Man (1970) – Director Mario van Peebles is no stranger to pushing buttons with the stories he tells, and this early 70’s gem is certainly no exception. The film stars Godfrey Cambridge as Jeff, a white racist who one day finds that he has somehow turned into black man, a discovery that, of course, he is repulsed and terrified by. From the fallout that ensues, van Peebles uses the farcical comedy of this premise to effectively showcase how Jeff (and indirectly, the audience) comes to realize just how disadvantaged people of color can sometimes be in a world predominantly controlled by white people. Even fifty years later, the film remains a jaw-dropper in terms of its subject matter, but that only makes the themes van Peebles conveys all the more relevant.

Killer of Sheep (1978) – Originating in the 1970’s and into the middle of the 1980’s was the LA Rebellion movement, in which black film students from UCLA took inspiration from the Roberto Rosselini and other filmmakers of the Italian neorealist movement, using techniques developed in this period to capture their worldview of black American culture. One such filmmaker was Charles Burnett, who uses this film to paint a picture of Watts, a predominantly black LA suburb and the effects poverty and social unrest has on its inhabitants. Aided by its semi-documentary style of storytelling, the film exemplifies the best of the LA Rebellion, with a scene showing children jumping from roof to roof standing out as one of the most iconic images of black cinema.

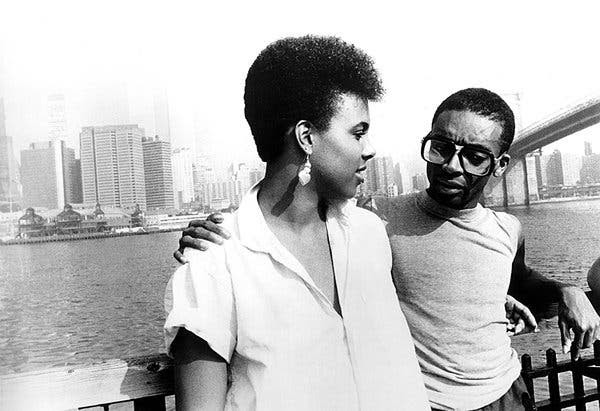

She’s Gotta Have It (1986) – To talk about the history of black independent cinema would be impossible without discussing one of its most iconic figures, Spike Lee. While Do the Right Thing remains his most popular work (and for good reason), his directorial debut, released three years earlier, is arguably just as impressive, or at least equally radical. While just as rooted in Lee’s urban New York upbringing as many of Lee’s works, this particular is unique in its depiction of female African-American sexuality. Revolving around a young Brooklyn-born black woman and the three men she engages in sexual activity with, this film was ahead of its time for its depiction of a black woman who finds freedom in multiple sex partners, loosely comparing monogamy to the act of slavery and portraying its protagonist’s control of her sexuality in a positive light, a theme that continues to hold merit over three decades since its release.

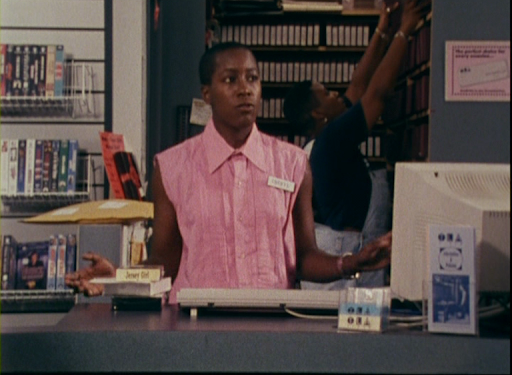

The Watermelon Woman (1996) – Starring, written, and directed by Cheryl Dunye, this mockumentary follows a fictionalized version of Dunye, a black lesbian (both in the film and in real life), as she attempts to create a documentary on the life of a forgotten black actress in the 1930’s rumored to have also been attracted to women. The film is a poignant reflection of the absence of disadvantaged people in film history discourse that blurs the line between fiction and reality through its documentary style, with the revelation of its titular figure being a work of fiction (outside the context of the film anyways) serving as a reminder of how crucial it is for up-and-coming filmmakers to look to people just like themselves for inspiration.

Middle of Nowhere (2012) – With a new century comes new filmmakers, and of the new talents to emerge from black independent cinema, Ava DuVernay is easily among the most noteworthy. Through this story of a woman contending with her husband’s prison sentence and the relationships she forms outside her marriage, DuVernay reflects on the plight of mass incarceration among African-American men, examining the effects that imprisonment has on its victims and its families. As further demonstrated by one of her later works, the Netflix documentary 13th, this is an issue that DuVernay takes very seriously; in crafting this narrative, she proves capable of addressing the complexities and hardships burdened onto those involved.

Fruitvale Station (2013) – before gaining worldwide recognition with the superhero blockbuster Black Panther, director Ryan Coogler crafted a much-smaller scale work of cinema that introduced many of the same themes that Coogler would come to incorporate into his following films. Recounting the tragic police shooting of Oscar Grant in 2009, the film showcases the life Grant lived and the relationships between him and his loved one, all of which came to an abrupt halt during a fateful encounter with an armed police officer. A predictor of sorts of the rising Black Lives Matter movement, the film maintains a place in American society as an embodiment of the well-documented struggle between African-Americans and certain municipal police forces.